The world of neuroscience has garnered renewed interest in a rather unlikely candidate: psychedelics. Known more commonly as mind-altering substances used in various cultural rituals or illicitly for recreational experiences, their therapeutic potential is now coming under scientific scrutiny. This blossoming field of interest centered around neuroscience and psychedelics has demonstrated promising leads, particularly their capacity for novel mental health treatment approaches.

Reliable clinical trials and brain imaging studies have started to strip away the stigmas and misconceptions that have cloaked psychedelics for decades. Pioneers in the integration of psychotherapy and psychedelics, like those at Johns Hopkins University and Imperial College London, have provided critical insights into how these substances trigger unique altered states of consciousness and may facilitate profound changes in mental wellbeing.

A key entity in psychedelic research is the group of serotonin receptors in the brain, particularly the 5-HT2A receptor. Studies show that psychedelics, such as psilocybin (magic mushrooms) and LSD, bind to these serotonin receptors, leading to a cascade of brain activity changes. However, the mere binding of the substances to receptors doesn’t fully explain the intricate subjective experiences reported by users, often described as mystical or deeply emotional. This is where advanced brain imaging comes into play.

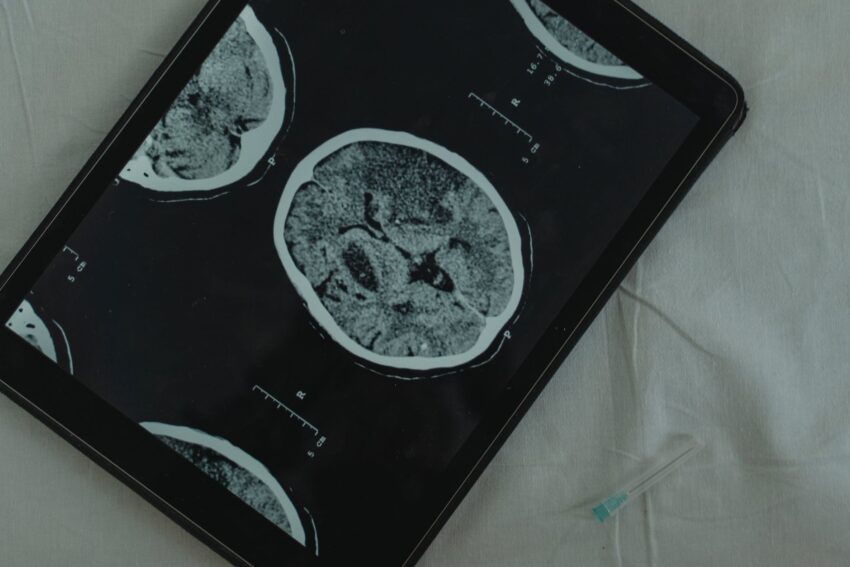

Neuroimaging offers a window into the brain’s operations when under the influence of these substances. Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) scans allow scientists to visualize real-time cerebral blood flow to various regions of the brain, indicating activity levels. Remarkably, psychedelics appear to induce a state of enhanced brain connectivity, forging links between areas that typically do not communicate.

According to brain imaging studies, under the influence of psychedelics, usual hierarchies in the brain are destabilized, freeing up cognitive resources and enhancing neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to form new neuronal connections and pathways. This has incredible implications for mental health treatment, particularly for disorders like depression, where brains often exhibit rigid patterns of negative thinking.

The potential benefits of these substances extend beyond the period of intoxication. In a number of clinical trials, even single doses resulted in enduring improvements in measures of wellbeing, life satisfaction and behavioral change. For instance, psilocybin-assisted therapy has recently been granted “Breakthrough Therapy” status by the FDA for treatment-resistant depression, based on preliminary results suggesting it offers substantially improved outcomes over existing therapies.

The benefits, however, are not solely linked to the chemical properties of the substances. The context in which the substance is administered, termed ‘set and setting,’ plays a significant role in determining outcomes. The role of psychotherapy, therefore, is integral. This is often coined as psychedelic-assisted therapy, involving careful preparation before the psychedelic experience, a therapeutic presence during, and comprehensive integration support afterwards.

While the promise of psychedelic research is encouraging, it is paramount to consider the potential risks and downsides. Inappropriate use can lead to harmful psychological effects, especially in people with underlying psychiatric conditions or those under uncontrolled and unsupervised circumstances.

With growing understanding and acceptance that treatment of mental illnesses needs alternative approaches, psychedelics are increasingly moving from counterculture into mainstream biomedical research and therapy. The profound effects of these substances on consciousness and neuroplasticity instigate substantially beneficial changes in emotionality, cognition, and behavior. Hence, their incorporation into mental health treatment protocols could trigger a paradigm shift in our management of psychiatric illnesses.

Sources:

1. Clinical trials

2. Serotonin receptors

3. Brain imaging studies

4. Psychedelic-assisted therapy